Dr. Shimizu’s research into the link between food and culture

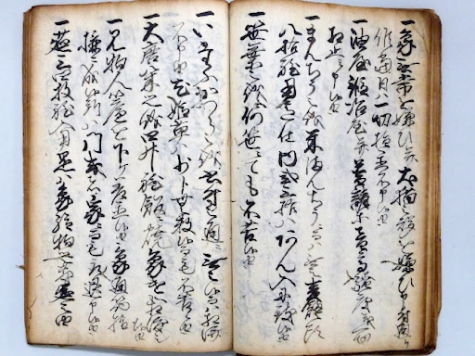

This is an example of kuzushiji, a form of Japanese cursive, translatable by Shimizu.

If you were to ask the average person for examples of what they consider “historically significant,” chances are that places like McDonald’s or their favorite local sushi restaurant wouldn’t be very high on their list.

But for one Wilkes professor, foods and food brands are always at the front of his mind when it comes to analyzing history and cultural development.

For over a decade, Dr. Akira Shimizu, assistant professor of history and global cultures, has been studying the link between Japanese cuisine and Japanese culture by deciphering documents that date back centuries.

“I call my methodology the “multimedia” approach,” said Shimizu. “It involves utilizing all kinds of food-related materials, including cookbooks, gazetteers that document regional dishes, diaries/memoirs, woodblock prints and illustrated books.”

By combining pieces of information gathered from varying sources, a fuller picture is gained of the foods produced, prepared and eaten by all classes within pre-modern Japanese society.

Often times the greatest challenge in employing this research methodology is simply locating and decoding the appropriate texts. The types of documents typically sought by Shimizu tend to be personal or archival in nature, meaning they very well may have been written down just once without any transcription into Modern Japanese.

This creates the two issues mentioned above; not only do these obscure records need to be rediscovered, the pre-modern Japanese “cursive” used by feudal writers must also be unraveled.

This is an example of kuzushiji, a form of Japanese cursive, translatable by Shimizu.

Fortunately, Shimizu is well equipped to handle both obstacles. He is one of only a handful of researchers in the United States capable of translating the calligraphy and typography seen in older forms of Japanese writing.

This gives him invaluable access to administrative documents pertaining to agriculture and food production in feudal Japan. Shimizu is also fully willing to travel wherever he needs to in order to find more information on a certain subject. Because of this, even a topic as seemingly mundane as grapes may necessitate a trip across the Pacific, provided there’s enough time to do so.

Now that the “how?” of food history has been answered we are brought to the next natural question. Why is any of this important?

Like any branch of history, its relevance derives from how events in the past have shaped our present. Modern Americans are a part of a “market culture” that gives them access to a massive variety of foods, with countless brands to choose from.

But the methods used by brands and corporations to produce and prepare food products didn’t just appear out of thin air, they evolved gradually over time and interacted directly with the cultures in which they developed.

“Today, Kobe beef has set a standard of the practice of food branding in Japan based on the place of production. I explore the beginning of this practice that can be found back in the late eighteenth century.” Shimizu illustrates. “In English and Japanese languages, there are no works on this topic.”

He also notes the role of cuisine when it comes to interactions between different social classes.

“I have discovered that region-based brand foods often served as an indirect medium through which the peasants and merchants were connected to or often influenced the dining table of the shogun—the highest political authority of Japan.”

While Shimizu’s main focus is on Japan, culinary traditions can be used to explore the history and culture of any country or people group, which is exactly what he teaches in his food history course.

Domingo Franciamore, senior history and education double major, elaborated further.

“The course, though it is titled food history, isn’t really a course about food throughout history but rather how food can be used as a lens to view time periods through. For instance the creation of modern ramen that we know today is the creation of the postwar relationship between the United States and Japan. Or how the landscape of food in Great Britain can be tied to the expansion of the British Empire. The physical class was more about Dr. Shimizu along with my fellow classmates and I, discussing our thoughts on the assigned readings.”

The course also requires a research paper. Franciamore chose to study how a large wave of European immigrants came to Argentina in the early 20th century and greatly influenced the local Spanish creole cuisine which had already been developed there.

Another former student, Robbie Petrovich, senior history and education double major, selected a research topic closer to home; he looked at how fast-food chains have impacted Northeastern Pennsylvania and presented his findings at the Wyoming Valley Undergraduate History Conference, which was hosted at Wilkes in 2018.

Petrovich states that while he did find the sheer volume of reading in the class to be difficult, it was ultimately a highly worthwhile experience with regards to his future career.

“Going into the course I really did not know much about Asia in general. The cool part is I have been able to apply what I learned in this course in other history courses I have taken at Wilkes, as well as my current student teaching placement at a local high school.”

Perhaps in the future, more students will be analyzing history with the help of the culinary arts, be it through learning about how ramen is made or about their local Taco Bell.

Shimizu has recently written a journal article, slated for publication this summer, about how the Japanese used smell to distinguish themselves from foreigners. His book project concerning Japanese food market regulations and their wider societal impacts during the Tokugawa Period is nearing completion.