Professor Emeritus Samuel Merrill publishes political research

Dr. Samuel Merrill, professor emeritus of computer science/mathematics at Wilkes University and Dr. Bernard Grofman, distinguished professor of political science at the University of California Irvine, published a research article in the Journal of Theoretical Politics titled, “What are the effects of entry of new extremist parties on the policy platforms of mainstream parties?”

Merrill was a professor at Wilkes from 1973 until his retirement in 2004 and taught courses in statistical analysis and computer simulation. He was raised in Bogalusa, Louisiana, and currently resides in Olympia, Washington. He received his bachelor’s degree from Tulane University and his Ph.D. in mathematics in 1965 from Yale University. He was also previously a professor at the University of Rochester from 1965 to 1973 and was also a visiting professor at the University of Washington Seattle and the Yale University School of Medicine.

He has authored three books on political science: “Making Multicandidate Elections More Democratic” in 1988, “A Unified Theory of Voting” (co-authored with Grofman) in 1999 and “A Unified Theory of Party Competition” (co-authored with James Adams and Grofman) in 2005.

Attempts to reach Merrill via email were not returned by the date of publication.

The journal article examines the consequences to center-left and center-right political parties in a two-party system when an extremist party at either end of the political spectrum enters said political system.

The article says that the entry of a single extremist party on either the left or right drives both mainstream parties in the direction opposite to the extremist party.

Gregory Chang, senior political science major, thought that the article’s findings made sense.

“Our electoral system isn’t going to allow for the rise of brand new third parties in this day and age, it’s just watching as people like Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump alienate moderate voters in each wing’s party and move them closer to the center, but it’s way more clear with Trump and moderate Republicans.”

New parties of many stripes may enter the political process, such as the Libertarian and Green Parties in the United States; however, it is a common phenomenon today, especially in European polities, for the appearance of an extreme party that substantially cuts into the support of centrist parties. Most commonly this extremist party is a populist party on the right.

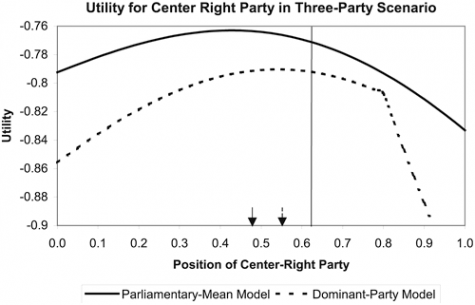

This graph tracks political utility under two different models. Political utility for both models drop as the center-right party’s political position moves to the right. The vertical line is the center-right party’s standard political position when there are only two parties.

This situation is modeled as a three-party system, with originally a center-right and a center-left party. This is followed by the entry of an extremist party, which turns the two-party system into a three-party system.

“I’m thrilled to see it empirically researched. You can just think of how some moderate Republicans have left the Republican Party or are just being more open to Democratic candidates in the face of Donald Trump’s presidency,” Chang said.

The article states this scenario has considerable empirical relevance in proportional representation settings such as the Netherlands, plurality settings such as the United Kingdom and in two-round elections such as France.

Although there have been cases of extremist parties entering the political space from both ends of the political spectrum, in recent decades it has most often been the right-wing party that becomes the greatest threat to the center in these kinds of systems.

In Europe, right-wing populist parties typically hold views that include anti-immigration, Euroscepticism (opposition to either parts of or the entire European Union), anti-environmentalism, neo-nationalism, anti-globalization, nativism and protectionism.

Throughout Europe, there are many examples of challenges to mainstream parties by more extremist parties. In the UK for example, UK Independence Party (UKIP), a right-wing populist political party, has gone from nowhere to being the largest British party in terms of members of the European Parliament.

Although winning only one member of parliament in the House of Commons, it received the third-highest vote share in the last parliamentary election. The importance of UKIP was enhanced because of the role it played in successfully lobbying for Brexit, due to the current likelihood of a hard-exit Brexit.

“There are many different examples. One would be the 2002 election in France with Jean-Marie Le Pen because every party banded together. The opponent, Jaques Chirac won 82 percent of the vote,” said Domingo Franciamore, senior secondary education and history double major.

Chirac was one of the least popular presidents in modern French history. However, Le Pen was universally reviled by both the left and the right, and held the same consistent views for decades. It was only when his daughter Marine inherited the National Front party, and rebranded it into the National Rally, that the position of the party morphed.

This involved purging her father from the party and rejecting anything directly supporting racism and anti-Semitism, and instead focusing on a strong nationalist anti-immigration stance. Now in France there is the potential for it to become its second most important party.

However, there are also long term trends that operate largely independently of the structure of the party system. Cited in the article, Sonio Alonso and Sara Claro de Fonseca’s 2012 study of 18 Western European countries over the period 1975–2005 said that mainstream parties on both the left and right have trended in an anti-immigration direction.

This was regardless of whether or not extreme right parties were present. In Austria, Germany, the Netherlands and Sweden, the mainstream left party moved in an anti-immigration direction before the emergence of significant far-right parties.

Merrill’s article was published in the July 2019 issue of the Journal of Theoretical Politics. He has published over 50 research articles in national and international refereed journals.

Parker Dorsey is a senior communications studies major with a concentration in strategic communications. Parker began as a staff writer for the opinion...